To quickly get started without writing any code, you can also use the zero-code fine-tuning interface to fine-tune your model on a dataset with a few clicks.

Notebooks for Fine-Tuning

Oxen.ai gives you the power to write custom code in Marimo Notebooks on a powerful GPU in seconds. This is a great place to write custom code and fine-tune your model. You can version your code, data and model weights all in one place, in a single repository.Example: Medical Question Answering

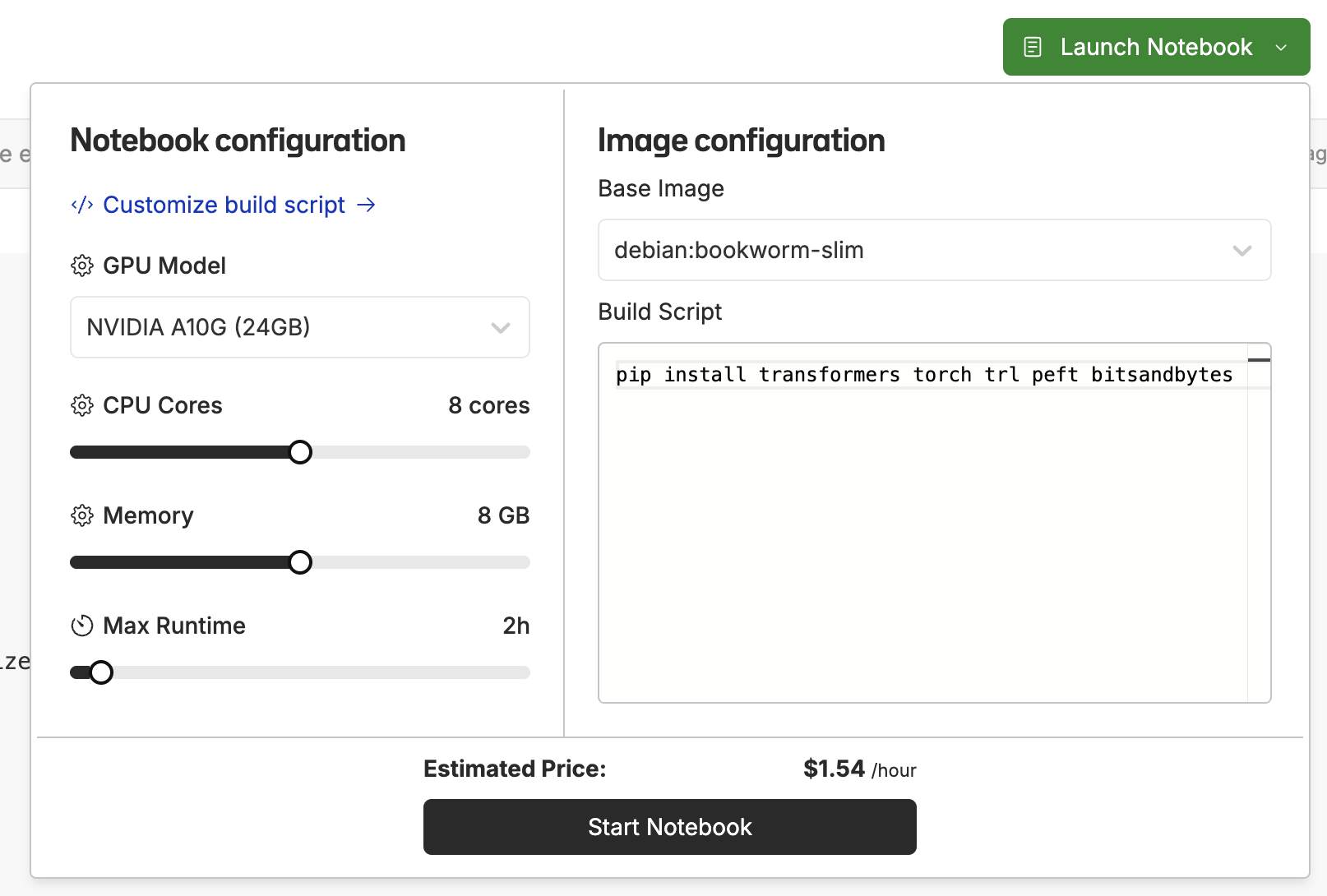

The domain of medicine is a good example where you might want to fine-tune an LLM. The domain is rich with nuance, and the data often has privacy concerns and cannot be shared publicly. If you want to follow along, you can run this example notebook in your own Oxen.ai account with the same data and model.Configure the Machine

Make sure to configure your notebook with an A10G GPU and the following dependencies. Allocate at least 2 hours, 8 cpu cores and 8GB of memory for the training to complete in a reasonable amount of time.

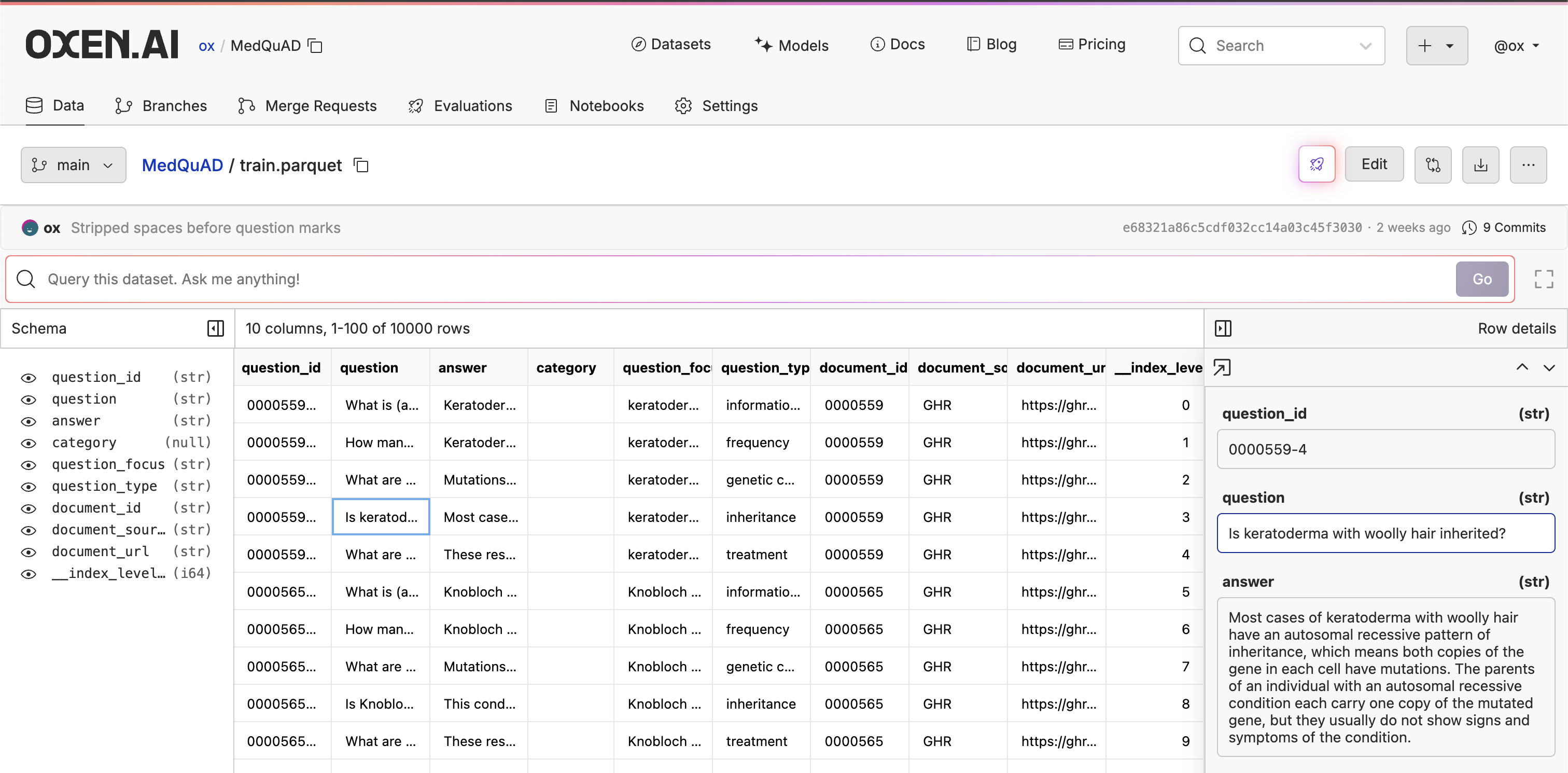

The Dataset

The dataset we will be using in this example is the MedQuAD dataset. MedQuAD includes 47,457 medical question-answer pairs created from 12 NIH websites (e.g. cancer.gov, niddk.nih.gov, GARD, MedlinePlus Health Topics). The collection covers 37 question types (e.g. Treatment, Diagnosis, Side Effects) associated with diseases, drugs and other medical entities such as tests.

load_dataset function from the oxen.datasets library. This is a wrapper around the Hugging Face datasets library, and is an easy way to load datasets from the Oxen.ai hub. To have fine-tuning work well, it is a good idea to have at least ~1000-10000 unique examples in your dataset. If you can collect more, that’s even better.

Don’t have a dataset yet? Checkout how to generate a synthetic dataset from a stronger model to bootstrap your own.

The Model

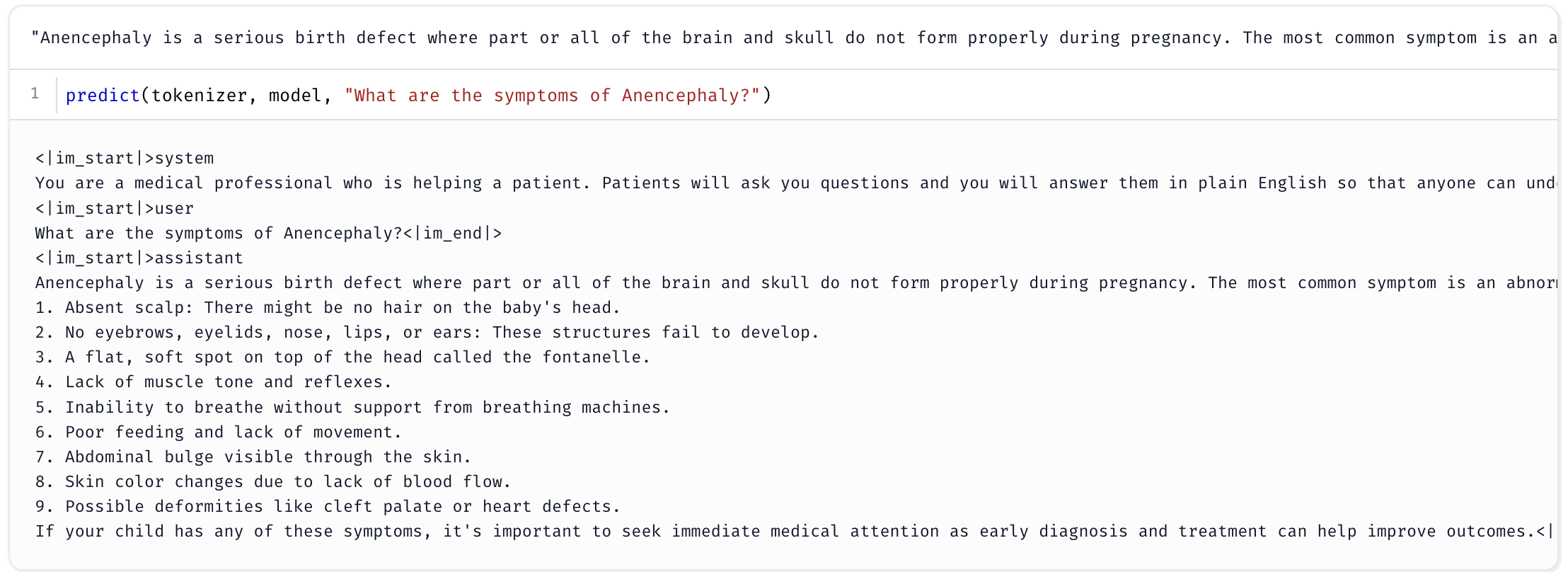

For this example, we will be using the Qwen/Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct model. This is a 1.5B parameter model that will be quick to train, and fast for inference. You can even download the weights and run on your laptop if you want. To load the model, we can use theAutoModelForCausalLM and AutoTokenizer classes from the transformers library.

predict function with a sample question.

Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning

To make our fine-tuning process more efficient in terms of memory and time, we can use a technique called Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning. This technique uses a technique called Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) to fine-tune the model. If you want to learn more about LoRA, check out the LoRA paper or our Arxiv Dive on the topic.Branches for Experiments

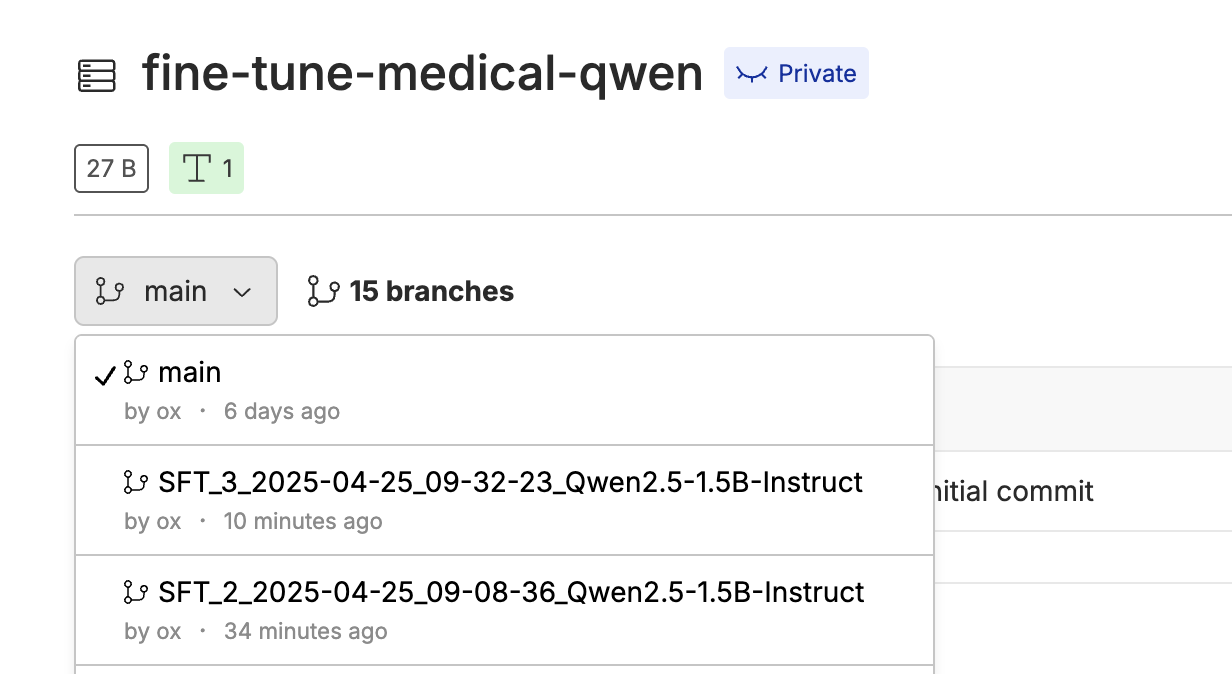

It is rare that you will get a fine-tune perfect on the first try. You must have an experimental mindset and be willing to iterate. In this case we will be simply saving the trained models and results to new branches on the same repository. We will setup anOxenExperiment class that will handle creating a new branch, saving the model, and logging the results.

Branches are light weight in Oxen.ai, and by default will not be downloaded to your local machine when you do a clone. This means you can easily store model weights and other large assets on parallel branches and keep your main branch small and manageable.

models directory to see the model weights and other assets.

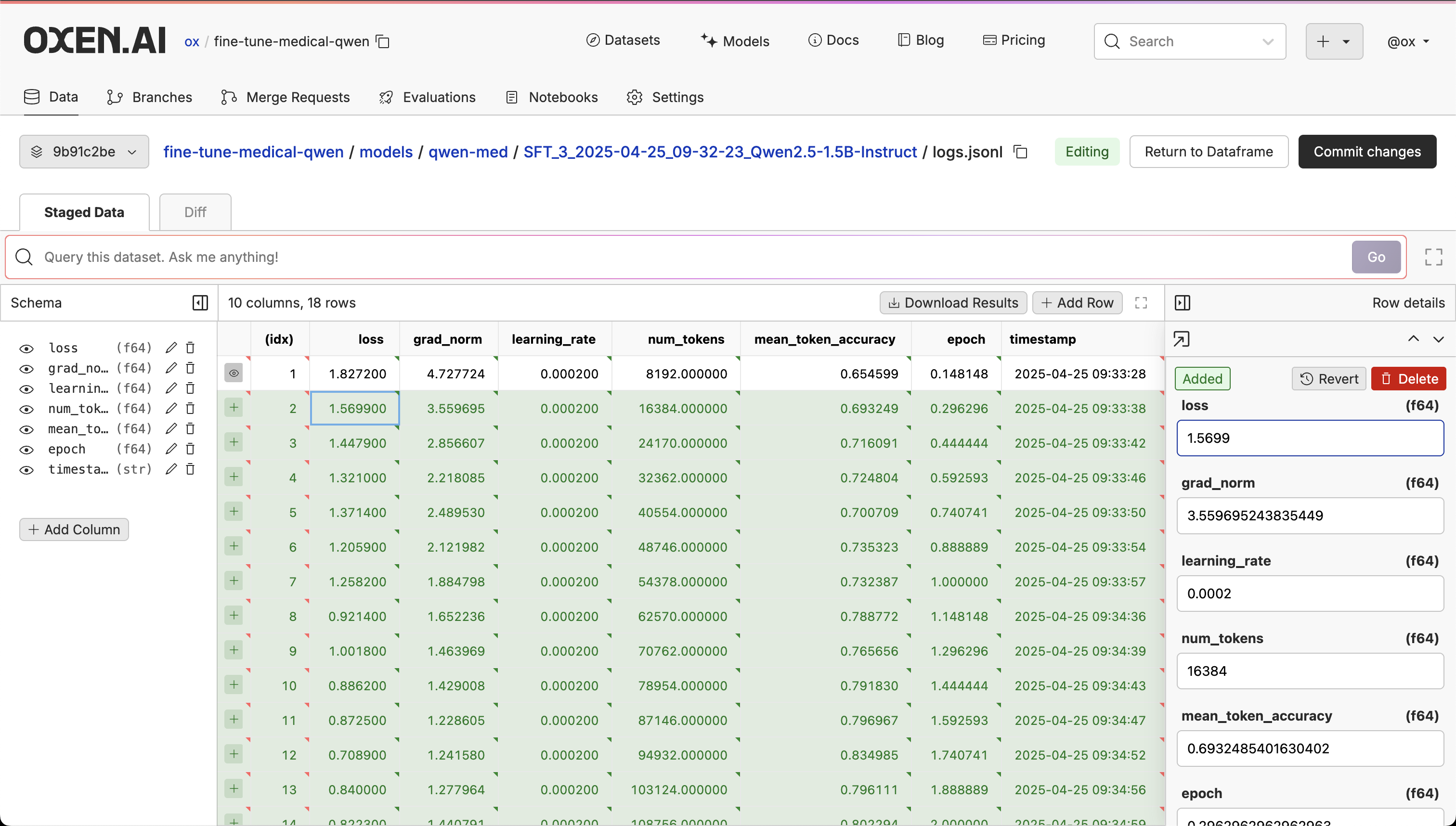

Logging and Saving

Once we have the experiment setup, we will want to reference it during training and log our experiment results. To do this, we will setup anOxenTrainerCallback that will be called during training to save the model weights and our metrics. This is a subclass of the TrainerCallback class from the transformers library, which can be passed into our training loop.

TrainerCallback class, we implement the on_save and on_log methods. The on_save method is called when the model is saved to disk, and the on_log method is called when the model is trained on a batch, reporting loss and other useful metrics.

The most important concepts here are the Workspace and DataFrame objects from the oxenai library. The Workspace is a wrapper around the branch that we are currently on. This allows us to write data to the remote branch without committing the changes to the branch. Think of it like your local repo of unstaged changes, but for remote branches. To navigate to your workspaces, use the branch dropdown and then look at the active workspaces for a file.

Workspace to write the temporary results, and then can commit the changes to the branch after training is complete.

on_log method.

RemoteRepo, model name, and output directory.

The Training Loop

Thetrl library from Hugging Face is an easy to use library for training and fine-tuning models. We can use the SFTConfig class to setup our training loop. This determines our batch size, learning rate, number of epochs, and other hyperparameters.